Using contact lenses is usually a safe experience, but they are not entirely risk free. Using contact lenses can increase the risk of certain eye problems, especially if the lens isn’t fitted correctly or if the wearer fails to follow the recommendations regarding wear schedule, discard schedule and hygiene. Underlying health conditions, such as a weakened immune system, can also increase the risk of experiencing problems with contact lens use.

Even if you are just using contact lenses for cosmetic reasons, you should still treat them with the same care as you would corrective lenses.

Below, you will find a few examples of eye problems that a contact lens user should be vigilant against.

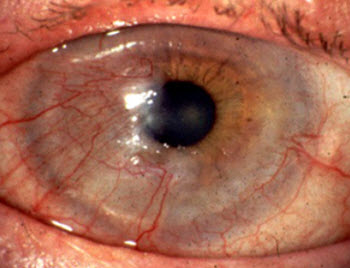

Corneal neovascularization

Corneal neovascularization is the excessive ingrowth of blood vessels from the limbal vascular plexus into the cornea.

Corneal neovascularization is the excessive ingrowth of blood vessels from the limbal vascular plexus into the cornea.

Corneal neovascularization is a reaction to the cornea not getting enough oxygen from the air. The most common cause of this is the use of contact lenses that do not let enough air through. Other examples of causes are corneal ulcers and herpes simplex.

The older type of hydrogel contact lense (made from materials such as 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) is more likely to cause corneal neovascularization than the newly developed lenses that have much better gas permeability. To put it simple: the more oxygen from the air that can pass through the lense, the lower the risk of corneal neovascularization.

When the cornea isn’t getting enough oxygen, the body will respond by growing more blood capillaries into the cornea to provide it with oxygen that way.

Advanced corneal neovascularization can threaten eyesight. This is one of the reasons why contact lens users should have their eyes checked by an optician once a year. The optician will be able to detect even early stages of corneal neovascularization.

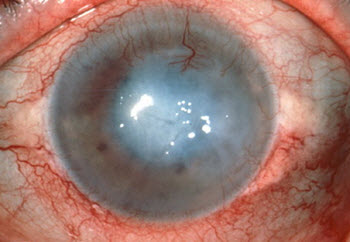

Keratitis

Keratitis is the Latin name for inflammation of the cornea. The cornea is the transparent dome that covers the iris, the pupil and the anterior chamber of the eye.

Keratitis is the Latin name for inflammation of the cornea. The cornea is the transparent dome that covers the iris, the pupil and the anterior chamber of the eye.

Many different pathogens can infect an eye and cause an inflammatory response, including bacteria, virus, fungi, amoebas and parasitic worms. Keratitis can also be cause by intense ultraviolet radiation exposure (e.g. snow-blindness). Exposure keratitis is a special type of keratitis that occur when the cornea gets dry because the eyelid fails to close properly.

Keratitis will typically cause moderate to intense eye pain. Other common symptoms are redness of the eye, a gritty sensation in the eye, sensitivity to light, and impaired vision.

With proper medical attention, keratitis will normally not lead to long-term visual loss. In serious cases, keratitis can scar the cornea and thereby limit vision. It is also possible for the infection to spread to other parts of the eye, and this can ultimately result in a complete loss of the eye.

Ulcerative keratitis

In an eye suffering from ulcerative keratitis, there is disruption of the cornea’s epithelial layer with involvement of the corneal stroma. A superficial ulcer will only involve loss of part of the epithelium. A deep ulcer will on the other hand extend into or even through the stroma. If the ulcer extends through the stroma, this is called descemetoceles and this is a condition that can rapidly result in corneal perforation.

Superficial ulcers will often heal within a week when the underlying reason for the ulceration is no longer present. Deep ulcers take longer to heal, and the patient may need conjunctival grafts, conjunctival flaps, soft contact lenses or even a corneal transplant. This is chiefly because a superficial ulcer can heal by epithelial cells migrating from the surrounding, healthy area. The healing of a deep ulcer is more complicated and will typically need an introduction of blood vessels from the conjunctiva to supply white blood cells and fibroblasts.

Contact Lens-Induced Acute Red Eye (CLARE)

This condition is typically acute with a very sudden onset. You can wake up abruptly in the middle of the night with serious eye pain and copious tearing. An eye suffering from CLARE will usually also be very sensitive to light.

This condition is typically acute with a very sudden onset. You can wake up abruptly in the middle of the night with serious eye pain and copious tearing. An eye suffering from CLARE will usually also be very sensitive to light.

It is not unusual for one eye to suffer from CLARE while the other eye is fine.

Most known cases of CLARE are associated with hydrogel contact lenses, although CLARE can develop in conjunction with other types of lenses as well, e.g. rigid gas permeable (RGP) contact lenses and silicone elastomer contact lenses.

Using extended wear lenses seems to increase the risk of getting CLARE. (These are the type of lenses that are kept in the eye around the clock, even when the wearer is aslepp.) CLARE is much less common in contact lens wearers that only use contact lenses while awake.

CLARE is more common during the first three months of using extended wear contact lenses, but can occur at any time.

What is CLARE?

CLARE is an inflammatory reaction in the anterior segment of the eye. The underlying reason is endotoxins released from gram-negative bacteria.

The anterior segment of the eye is the front third of the eye; the part that includes the cornea, the iris, the ciliary body and the lens.

Examples of gram-negative bacteria that have been isolated from eyes suffering from CLARE are Haemophilus influenzae, Pseudomonas spp and Serratia spp.

Interestingly, the specific bacterial strains that are associated with CLARE differs from strains of the same species causing corneal ulceration.

What to do

If you suspect that you have CLARE, immediately remove the contact lens. (Ideally, remove them from both eyes even if only one eye is showing symptoms.) Then seek medical attention to make sure that it is actually CLARE and not something else.

The body can usually handle CLARE on its own without medical aid, as long as the eye is kept free from the contact lens. This can take several weeks.

In some cases, antibiotics will be required to get rid of CLARE. Being prescribed 48 hours of topical antibiotics is especially common if there is any epithelial disruption.

Steroids can be prescribed to reduce inflammatory response, but their use in the treatment of CLARE is debated.

Corneal abrasion

Corneal abrasion involves the loss of the surface epithelial layer of the cornea. It is usually the result of corneal dystrophy or a complication following trauma to the surface of the eye, e.g. walking into something or being poked in the eye. Improper use of contact lenses can also cause sufficient trauma for corneal abrasion to occur. Removing a CL that has been left in the eye for too long is especially risky.

Corneal abrasions will normally heal on their own as long as the trauma isn’t sustained, but medical attention can be required to prevent complications, such as pathogens infecting the damaged cornea.

N.B! If the healed epithelium doesn’t adhere properly to the underlying basement membrane, it may detach at intervals and give rise to recurrent corneal erosions.

Recurrent corneal erosion

Recurrent corneal erosion is a very painful condition and it can also cause temporary blindness. In a patient with recurrent corneal erosion, the cornea’s outermost layer of epithelial cells fails to attach to the underlying basement membrane. This causes sensitive corneal nerves to be left exposed and the eye becomes extremely sensitive to light (photophobia).

A person with recurrent corneal erosion typically has a history of previous corneal injury, such as corneal abrasion or corneal ulcer. Certain corneal diseases and dystrophy can also lead to recurrent corneal erosion.

Cosmetic contact lenses

Cosmetic contact lenses